Birds in Big Numbers: Snow Geese in Spring Migration

by Joanna Reuter

Part three in an occasional series, Birds in Big Numbers

If you want to see as much biomass of a single bird species as possible, at one place and time in the state of Missouri, what should you be looking for? A blackbird roost hosting millions of birds? Nope. A high-density commercial poultry house? Nope. A concentration of Snow Geese at a stopover during northbound migration? Yes!

Let’s look at what’s been reported on eBird in the Columbia Audubon Society (CAS) six-county region:

Regional high count: An estimated 1.1 million Snow Geese at mid-day on Tuesday March 5, 2019 at Thomas Hill Reservoir in Randolph County:

My favorite part about this eBird list by Brad Jacobs and Paul McKenzie is that they used satellite imagery to supplement their field estimates. Reading between the lines, even two of the state’s most experienced birders found it challenging to estimate numbers within two vast flotillas of geese. One flock extended for about two miles down the lake, but how wide was it? A SkySat image allowed them to measure the area occupied by the flock and refine their total estimate.

Missouri high count: The state high count record on eBird was reported by Thomas Oots at Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge on March 17, 2014, and included the following spectacular video:

Given inherent uncertainties in estimating the size of large flocks, can we truly say that this observation is definitively “the” high count of Snow Geese as witnessed and reported by an eBirder? Is 1.4 million really differentiable from 1.35 million or even 1.3 million? It’s certainly true that Loess Bluffs NWR is the eBird Hot Spot in Missouri with by far the most reports of a million or more Snow Geese. Its location in the Missouri River valley in northwest Missouri makes it a good stopover site for geese, and those big numbers come with a certain credibility as many eBirders note that reported numbers are based on routine counts by refuge staff experienced in making such estimates. For example, the comment for the 1.4 million bird estimate notes:

“Staff biologist advised that a count a day prior was 1.4 million birds. I was advised that they determine count by the acre. Obviously impossible to photograph all from the ground.”

Migratory context:

Snow Geese tend to migrate by interspersing long-distance flights with stopovers for resting and feeding. In the USGS animation below, each color represents a goose that was tagged with GPS and monitored to track its location. The tracks begin in late summer when the tagged geese were in northern Alaska; the animation follows them through southbound migration, overwintering, and northward return in spring.

You can clearly see how periods of relative stability in a particular location tend to be punctuated by long, rapid movements to new locations. This pattern is consistent with eBird data showing that when a lot of geese stop at a given location, flocks often stick around for a few days. But they can fly long distances between stops.

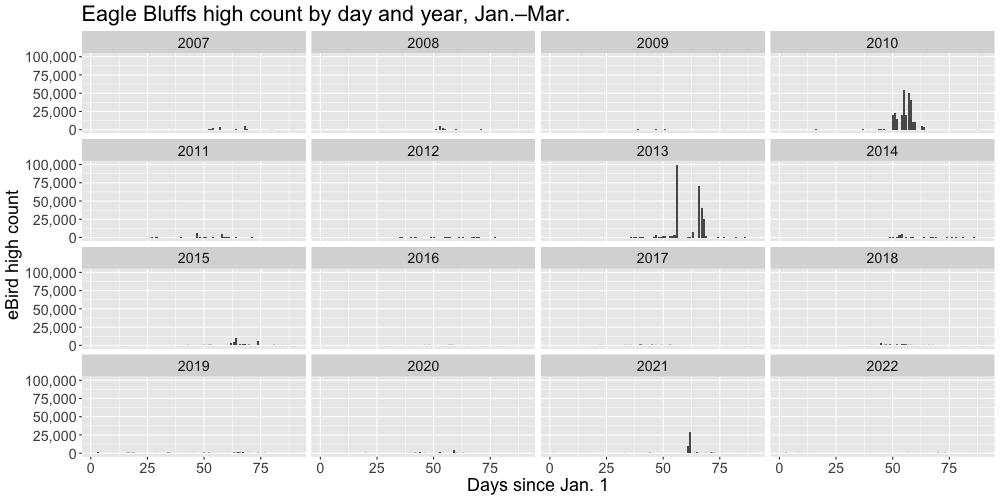

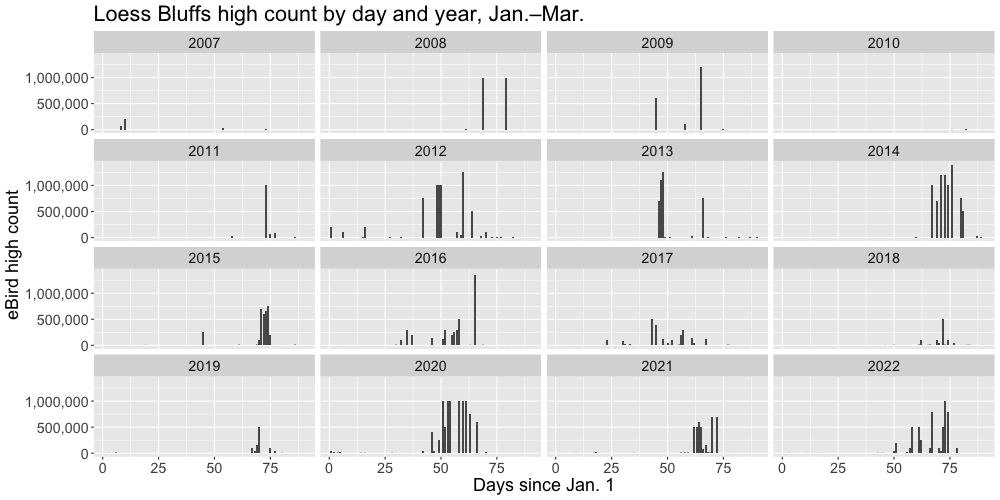

When (time of year): In central and northwest Missouri, peak Snow Goose concentrations tend to occur between the middle of February and the middle of March. The plot below shows the highest Snow Goose count on a given day, for that location, for all years available on eBird.

When (time of day): Snow Geese aren’t as picky about time of day for migration as other birds. For example, most songbirds migrate at night, while raptors migrate during the day to take advantage of thermals, but geese will fly night or day.

When (weather): Weather definitely plays a role in Snow Goose migration, with factors including temperature, ice conditions, fronts, and wind all affecting their behavior. We find this weather website especially useful for envisioning large-scale weather patterns that might influence migration.

Where (for viewing geese in the air): From just about anywhere in central Missouri, you can view Snow Geese migrating overhead if you happen to be there at the right time. Simply pay attention when you’re outside, and perhaps find a place with a decent sky view. Listen for their distinctive vocalizations; we often hear flocks before we can pick them out by eye. It is quite possible to see extraordinary numbers of geese flying overhead from your yard or a nearby park.

Where (for viewing geese on the water/ground): eBird datasets help illustrate when conservation areas and wildlife refuges have hosted large flocks of Snow Geese.

- Eagle Bluffs Conservation Area (see graph below) hosted tens of thousands in 2010 and 2013, but it doesn’t seem to be a dependable annual stopover location for big flocks.

- Grand Pass Conservation Area hosted between 100,000 and 1,000,000 in 2009, 2014, 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2022. Are Snow Geese using the area more in recent years, or are more eBird lists being submitted, or both?

- Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge (see graph below) has recorded over a million in numerous years, and even the “low” years typically max out with hundreds of thousands.

- Thomas Hill Reservoir doesn’t appear to be a routine stopover location, but eBird records there are also especially sparse.

Maximum count of Snow Geese reported for each day (January through March) of the specified year at Eagle Bluffs. Although the total numbers don’t come close to Loess Bluffs, I have fond memories of being dazzled by an impressive abundance of Snow Geese in 2010.

Maximum count of Snow Geese reported for each day (January through March) of the specified year at Loess Bluffs. The timing and duration of peak Snow Goose numbers varies from year to year. Also note that the number of eBird lists varies over time, with more thorough coverage in recent years.

When (duration): When Snow Geese do visit a refuge or other stopover location, large numbers can often persist for a number of days, even more than a week. But there’s never a guarantee! If you don’t have time to scout locations on your own, the best chance of seeing Snow Geese in quantity is to go to the site as soon as possible after someone else reports large numbers there.

Why so many? Snow Goose populations have changed dramatically over time.

Once upon a time, Snow Geese of the central continent migrated to the Gulf coast for the winter, only passing though Missouri during migration (Alisaukas, 1998). Now, times have changed, and many overwinter in Missouri as well as other non-coastal areas of the south-central United States. What happened?

One major factor involves a dietary shift. Instead of just feeding in coastal marshes, Snow Geese discovered waste grain left in agricultural fields (rice in the deep south, and corn further north). As this became a major component of their winter diet, overwintering expanded across a much broader region, coinciding with a dramatic increase in population (Alisaukas, 1998).

This spike in population triggered concerns about summer nesting habitat and tundra damage, leading to the Light Goose Conservation Order, which expanded hunting opportunities in an effort to control the exploding population. This didn’t work as well as hoped, though populations seem to have leveled off a bit (USFWS, 2022).

What the future holds for Snow Goose populations is unclear. One factor of current relevance is the ongoing outbreak of bird flu (or Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, to be precise). Since the beginning of the outbreak in 2022, official records have documented 52 Snow Goose deaths in Missouri (including one from December 2022 in Boone County). The broader implications of this remain to be seen. If you encounter a sick or dead wild bird that you think may be bird-flu related, please report it to MDC.

Field trip: We’d love to schedule a goose-watching field trip, but it’s clear that predicting place and time weeks or months in advance is very much a gamble. However, if big numbers of Snow Geese are reported at a nearby stopover, a quickly arranged field trip has at least half a chance of getting there in time (and, if not, there are sure to be other things to see). So, if you’re feeling inspired to see a lot of geese, keep an eye on the sky, MOBIRDS, and your email (subscribe to CAS notifications here)!

Data source: eBird Basic Dataset. Version: EBD_relOct-2022. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Oct 2022.

Learn more: Here are some additional resources to explore:

Alisaukas, R.T., 1998, Winter range expansion and relationships between landscape and morphometrics of midcontinent Lesser Snow Geese, The Auk, 115: 851–862. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4089504

Loess Bluffs Waterfowl and Bald Eagle Surveys for recent months are available online.

Loess Bluffs waterfowl surveys: https://www.fws.gov/library/collections/loess-bluffs-waterfowl-and-bald-eagle-surveys

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Waterfowl Population Status, 2022. https://www.fws.gov/media/waterfowl-population-status-2022

Text © Joanna Reuter 2023