Birds in Big Numbers: Migratory Chimney Swift Roosts

by Joanna Reuter

Part four in an occasional series, Birds in Big Numbers

Chimney Swifts are master flyers that spend virtually all daylight hours on the wing, fueling their flight with a diet of insects. As long-distance migrants, they spend the summer breeding season in North America and the winter in South America. Commonly described as “cigars with wings” due to their distinctive body shape, these cigars don’t smoke, and neither do most of the chimneys with which they are now so commonly associated. Where did they roost before chimneys became an option? Natural roost sites include hollow trees and caves. But if your goal is to see a Chimney Swift extravaganza, you should probably plan for an evening in town rather than a trip to a remote wild area.

Above: Chimney Swifts in flight. Photos by Chrissy McClarren and Andy Reago, via iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/87211923 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/112233926).

During fall migration, Chimney Swifts use communal nighttime roosts, which commonly host hundreds of birds, though some roosts can host thousands at the peak of migration. Roosts are fun to watch: birds gather at dusk, circle in an ever-tightening cloud that can resemble a tornado run in reverse, and drop down into the roost site as darkness descends.

Boone County high count: According to eBird, the high-count record for a roost site in Boone County is at the Armory building in downtown Columbia, where Cheryl Rosenfeld reported an estimated 1,000 birds on October 11, 2021 (eBird checklist). For years, this has been a known roost site, where numerous eBird reports document counts of hundreds of Chimney Swifts during fall migration.

Above: Birder and author Noah Strycker photographed the roost during his 2021 visit to Columbia on an evening when he and fellow observers viewed an estimated 500 Chimney Swifts, according to the eBird list.

Missouri high count: Springfield currently holds the state high-count record during fall migration, with several counts in different years totaling between 1,800 and 2,200 birds. Several of these records come from roost-watch field trips hosted by the Greater Ozarks Audubon Society (GOAS). Since 2011, an annual GOAS field trip in early September has included a Chimney Swift count (L. Berger, personal communication). This site is unusual in that no chimneys are involved, but rather these four hollow, concrete columns.

The roost count eBird lists include notes about how many swifts used each column. Interestingly, swifts tend not to distribute themselves evenly among the columns.

Continental high count: The single biggest concentration of Chimney Swifts documented on eBird is at a chimney in a Detroit suburb (Farmington) that has been designated as a Swift Sanctuary. Peak numbers occur during fall migration, with multiple reports in the tens of thousands and a peak estimate of 50,000! Not surprisingly, it takes a large, abandoned chimney (151 feet tall) to host this many birds.

Where (in general): Chimney Swifts can certainly nest in small, residential chimneys, and some even still use hollow trees. However, my impression is that larger, urban chimneys are commonly the sites of large fall roosts, as seems to be the case in Columbia. Why is this? Is it the size of urban chimneys that they like, because they’re big enough to hold a lot of birds? Is the urban heat island a factor, providing a boost of warmth on chilly fall nights? Is an urban area a good foraging zone, with thermal air currents concentrating prey insects in ways that can be thought of as “aerial plankton” (Wheeler, 2012)? Are urban lights a factor in feeding, even though the birds tend to roost before full dark? Is it all of these, or something else? Regardless, urban roosts are fun and easy to watch, and have the potential to draw the attention of more people towards birds, though I’ve been surprised to watch people walk right past an active roost, oblivious to the avian wonder overhead.

When (time of day): Chimney Swifts come to roost in the evening, as the sky is darkening. Roost entry often begins roughly 20 minutes after sunset, but weather conditions (clouds, temperature, rain) may influence exact timing.

In the morning, roost departure begins an average of 11 minutes before sunrise according to Birds of the World; several eBird lists from Missouri support this approximate timing. If you’re an early riser, consider a visit to observe morning departure, and please write a description of what it’s like, as I haven’t found one (or experienced it first-hand, yet).

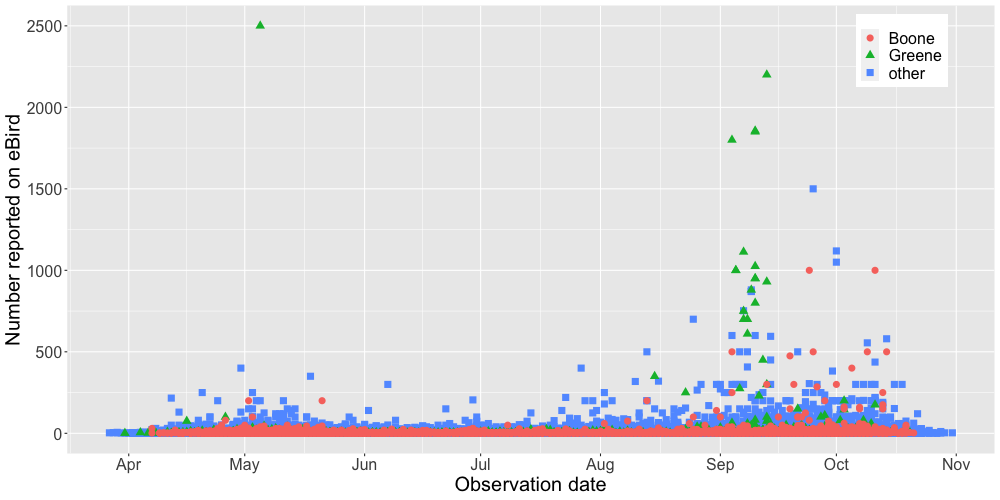

When (time of year): eBird data provide some constraints on the best date range to look for big numbers of Chimney Swifts. Here’s a plot:

Above: Scatterplot of Chimney Swift counts by day of year, from eBird lists for Missouri. Points for Boone County (including Columbia, in red) and Greene County (including Springfield, in green, naturally) are plotted on top of the combined statewide points from other counties (blue).

One caveat: There’s been no systematic monitoring via eBird in Missouri to determine the best timing to see peak numbers of migrating Chimney Swifts. The Greene County (Springfield) points are clustered in early September due to the traditional timing of the GOAS count, implying that early September can be a good time to watch. Observations in Boone County suggest that high counts can also occur a bit later, though these aren’t based on systematic sampling.

Generally, the potential for high migratory numbers seems to be best from early/mid September through mid-October. But what about the details? How much do numbers vary day-to-day, how long are individuals staying, and what’s the overall flux through the area?

We don’t have the data to answer these questions now, but with time, perhaps we will. A combination of old-fashioned and high-tech methods may yield the best answers. As citizen scientists, we can take part in old-fashioned roost monitoring by counting birds and submitting results to eBird. And, in time, MOTUS will also yield insights. Already, Chimney Swifts are being tracked by the MOTUS network, though so far the birds that have been tagged are mostly based on breeding grounds in the northeastern US and eastern Canada, and so results are less directly relevant to migratory pathways through Missouri.

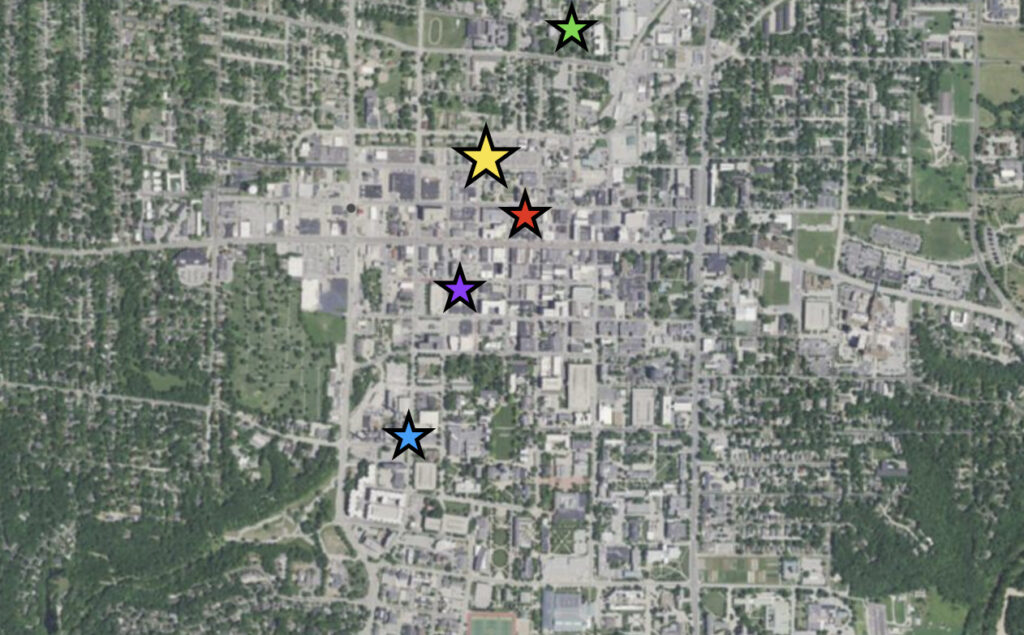

Where (in Columbia): The chimney on the east side of the Armory building, located on the northeast corner of N 7th Street and E Ash Street, seems to be the most consistently used roost in Columbia (or at least the one most consistently observed by eBirders). However, at times, other sites may be used in addition to (or instead of) the Armory site, as shown in the following map:

Sites with reports of fall roost activity in Columbia, from north to south: a building on the Columbia College campus (green), the Armory (yellow), a building at the southeast corner of Walnut and 8th (red), the Federal Building at 6th and Cherry (purple), and a building near the power plant at 5th and Stewart (blue). (Locations from eBird and J. Besser, personal communication.)

These sites are all in the most urbanized part of Columbia, but roost sites aren’t necessarily limited to that area. For example, a September 10, 2012 MOBIRDS listserv message reported 1,000 Chimney Swifts roosting in a chimney at West Junior High.

Although the focus of this article is on Columbia, I’m curious whether roosts also occur in smaller urban areas with industrial histories, such as Sedalia, Moberly, Centralia, and Mexico. I’d guess that more roosts occur than are documented on eBird at present; keen observers who take the time to check these non-traditional birding locations and report on eBird may fill in some knowledge gaps.

Conservation concern and citizen science: Population estimates of Chimney Swifts show a declining trend over recent decades, but why? Are insects—a necessary food resource—in decline, perhaps due to substantial increases in pesticide use (USGS pesticide use data)? Are nesting and/or roosting habitats limiting factors? Are there limiting factors associated with migratory corridors or overwintering habitat? The degree to which each of these matters is unclear.

Estimating populations of birds at a continental scale is difficult. But fall roosts of the sort that occur in Columbia serve to concentrate birds and provide an opportunity for an alternative way to put a finger on the pulse of what’s happening over time. Wouldn’t it be neat if we—as a community—took it upon ourselves to monitor these roosts, learn the patterns of activity, and—if done for enough years—assess the trends over time? And think about all of the passers-by who might be drawn into the birding community if they happen to be present when someone in the know is also there to explain the basics of this cool thing they’re seeing (no, they’re not bats, they’re birds, they’re on a migratory path to South America, and just think of all the bugs they’re eating along the way!).

One more factor with regard to conservation: Since the big chimneys that swifts often prefer for fall roosts tend to be old, and new construction doesn’t provide an equivalent, there’s a potential for advocacy to ensure that important roosting chimneys are recognized, appreciated, and preserved.

Swift counting and other eBird reporting suggestions: Counting swifts can be a bit challenging. You can definitely appreciate the spectacle without knowing how many there are, but if you’re reporting to eBird, it’s good to try to get a reasonable estimate. Our experience is that some will disappear down the chimney while others are still arriving, so there’s never an opportunity to view all of them simultaneously for a total numbers estimate. The most effective strategy we’ve used is to keep an eye on the chimney’s mouth and count birds as they disappear down into it.

On slower nights, it may be possible to count one by one, but big nights require some estimation as multiple birds drop in simultaneously. Also, be aware that some birds will make a close approach to the chimney but not drop in, opting to circle again instead. This all happens while darkness is intensifying, making counting more challenging than it appears! The good news is that, once in the chimney, they seem to stay there until morning. Count what goes in, and count fast. Or, rather, swiftly.

If submitting an eBird list, it can also be helpful to note the time that the first and last birds disappear into the chimney, as well as weather conditions (temperature, cloud cover, precipitation). If you go to a roost site, and few or no birds show up, that’s also useful information to report.

News flash! Columbia’s Armory roost site very recently received designation as an eBird hotspot, so if reporting for that site, please use the hotspot, and if you have older lists, please consider adding these to the hotspot.

Field trips: In 2023, CAS will be hosting three field trips to watch this fascinating phenomenon. Past eBird reports informed the location and dates, but past data can’t always predict the future, so if advance scouting suggests we should tweak locations, we will. Please help us scout! Share observations of concentrated Chimney Swift activity through one or more of these methods: eBird, the MOBIRDS listserv, and/or an email to cherthollow@gmail.com (Eric and Joanna Reuter).

See the field trip listings for full details:

- Tuesday, September 19 at 7:00 p.m. (sunset: 7:11 p.m.), led by Jim Gast.

- Friday, September 29 at 6:45 p.m. (sunset: 6:55 p.m.), led by Eric and Joanna Reuter.

- Monday, October 9 at 6:30 p.m. (sunset: 6:39 p.m.), led by Eric and Joanna Reuter.

These trips are especially suitable for new and/or young birders, as they don’t require binoculars or any particular knowledge, just enthusiasm and a free hour of an evening. We hope many folks will join us in raising our awareness of, and knowledge about, these awesome birds, as they honor us with a visit on their long journey!

Data source: eBird Basic Dataset. Version: EBD_relJun-2023. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Jun 2023.

Learn more: Here are some additional resources to explore:

Cornell’s Birds of the World online (access by subscription) has detailed species accounts that informed this article.

To get an idea of what a Chimney Swift roost looks like, check out this video from North Carolina. And for some more amazing swift footage, though they’re Vaux’s Swifts, not Chimney Swifts, see this video from Portland, Oregon.

If you happen to be in Springfield on September 9, be sure to take part in the Greater Ozarks Audubon Society Swifts and Sundaes field trip, 2023 edition.

Regarding the Swift Sanctuary near Detroit: The Detroit Audubon website has a neat photo down into the chimney, and (at times) a webcam of the roost. Here’s a more detailed account of the roost.

Wondering what MOTUS is? Check out this webinar in which Sarah Kendrick explains.

Text © Joanna Reuter 2023