Overwintering Trumpeter Swans Increasing in Missouri

by Joanna Reuter

Two adult and two juvenile Trumpeter Swans in corn stubble at Bradford Farm (Boone County, MO) on January 3, 2018. Photo by CAS member Kathleen Anderson; used with permission.

by Joanna Reuter

Four years ago this month, Eric & I first saw Trumpeter Swans flying over our northern Boone County property. What seemed an amazing novelty then has become a common occurrence during the winter months, but we still experience a thrill with each passing flock, typically announced by a distinctly nasal honking. Sometimes they never come within view, but often a flock will cruise low overhead, close enough to hear the whistling of wind through wings. Frequently, several flocks are grouped within a few minutes to half an hour; we’ve seen close to 60 individuals pass over in a single day. Our winter sightings fit into a broader trend of increasing swan numbers in Missouri, itself part of the return of a breeding population to the Upper Midwest after extirpation in the 1800s through hunting and habitat loss.

Trumpeter Swans could aptly be described as charismatic megafauna. Just how mega- are they? Other sizable birds in Missouri include the Bald Eagle (6.6–13.8 lb), Canada Goose (6.6–19.8 lb), and Wild Turkey (5.5–23.8 lb), using the typical weight ranges reported on Cornell’s allaboutbirds.org. Envision the ungainly effort required to get a turkey airborne before considering that Trumpeter Swans are even more substantial birds with a typical weight range of 17–28 lb (with males generally larger than females). A record turkey might outweigh an average Trumpeter Swan, but the swan, unlike the turkey, is capable of lengthy and graceful migration. Like a turkey, takeoff requires significant effort: “Getting airborne requires a lumbering takeoff along a 100-yard runway”. With a wingspan that can exceed six feet and a length that can exceed 5 feet, the stylish flight of a Trumpeter Swan is a memorable sight to behold.

Charismatic megafauna are more than just big: They have a certain charm that motivates people to act and contribute funds on their behalf. Trumpeters are among the few species with a dedicated non-profit organization; The Trumpeter Swan Society is dedicated to the restoration and conservation of their populations. This society, along with other partners including federal and state governments, undertook captive breeding and other efforts to re-establish populations of Trumpeter Swans in parts of their former breeding grounds. That range once spanned the North American continent from coast to coast, including the Upper Midwest as far south as Missouri and northern Arkansas.

Reintroductions of Trumpeter Swans began in the 1960s in Minnesota, in the 1980s in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ontario, and in the 1990s in Iowa, according to both Wikipedia and The Trumpeter Swan Society. Though there were some failures along the way, the programs were collectively extremely successful, with a dramatic trend of increasing population in recent years. To my knowledge, no attempts have been made to introduce breeding pairs to Missouri. At least a couple of pairs have nested successfully in Missouri in this century, based on references in the Mobirds listserv archive to nests in Carroll and Livingston Counties. However, the vast majority of Trumpeter Swan observations in Missouri occur during winter (see figure below); these are birds that migrate to our balmy state from more northerly locations.

Trumpeter Swan high count by month (based on eBird data through November 2017) for Missouri (left) and Boone County (right). Note the different y-axis scales. Data source: eBird Basic Dataset. Version: EBD_relNov-2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Nov 2017. Plot by Joanna Reuter.

For a reintroduced swan, learning to migrate is a non-trivial matter. According to The Trumpeter Swan Society, one challenge in our region is the “need to create new migration traditions between nesting and wintering grounds. The tradition of migration is a learned behavior and was lost when swans were removed from the region over a century ago”. A variety of strategies can be used to teach the birds where to go. Trumpeters near the East Coast have been led along suitable migration routes using ultralight aircraft. Another strategy is to physically move birds to a new location in hopes that they will imprint on the area and return to it. For example, the September 1982 issue of The Bluebird (the Audubon Society of Missouri newsletter) describes a plan to bring a family of Trumpeters from Lacreek NWR in South Dakota to Mingo NWR in southeast Missouri. I was unable to determine whether that particular effort was successful.

One way or another, Trumpeter Swans did start migrating to Missouri again. The Bluebird from June 1985 states: “The unprecedented migration of 29 Trumpeter Swans from the Hennepin County, Minnesota restoration flock in December sparked a flood of interest and increased awareness of migrant swans throughout the state…. Ten of these wore yellow collars indicating they were Trumpeter Swans that had originated from that Minnesota flock and eight could be seen closely enough to confirm collar numbers and verify that origin.”

Now comes a snag as far as official birding records are concerned. Extirpated species aren’t technically countable, but this once-extirpated species started showing up again in Missouri. However, the reintroduced Trumpeters required substantial help from humans. The first individuals to migrate to Missouri were likely released birds, and those weren’t considered wild, so they were ruled uncountable for records. But at what point is counting allowed again as they become re-established? (There’s an interesting discussion on the Mobirds listserve about this from July 2003, including these posts). How do you know if a bird was raised in captivity or not? Collars and tags with identification may help, but they don’t always provide a definitive answer. How do you define when a bird is wild enough to count? Even as late as 2006, the Missouri Bird Records Committee rejected a Trumpeter Swan sighting because it was a “potentially human-assisted bird.” I see the dilemma, but with the benefit of hindsight, I’d love to have access to a more complete collection of records that reflects the full arc of Trumpeter Swans’ return to Missouri.

High count by winter for all of Missouri (left) and for Boone County (right) based on eBird data. Each bar represents the maximum number of swans reported on a single eBird list for a one-year period from fall through spring (labeled with the earlier year, i.e. 2015-2016 is labeled as 2015). Note the different axis scales. Since 1993, all of the Missouri high counts are from Riverlands (north of St. Louis along the Mississippi River). The Boone County high counts are from Eagle Bluffs Conservation Area, with two exceptions: the high counts for the winters of 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 were from flyover flocks at Chert Hollow Farm in northern Boone County (a surprise to us!). The 2017-2018 high count is provisional and subject to change. Data source: eBird Basic Dataset. Version: EBD_relNov-2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Nov 2017. Plot by Joanna Reuter.

In any case, today’s Trumpeter Swans are fully countable in Missouri and their numbers are rising. Archived content from Mobirds and The Bluebird make mention of birds with collars, confirming that some migrants were coming from Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Iowa (for example, see the June 1995 issue of The Bluebird or this example Mobirds post). What’s the attraction of overwintering in Missouri? Our relatively mild winter climate usually has ice-free water available, particularly on the big rivers. Some smaller bodies of water are also managed in ways that maintain ice-free conditions; for example, a small private lake east of Highway 151 just north of Sturgeon appeared to have open water and a sizable congregation of swans and other waterfowl on a day in early January when even the much larger Rocky Fork Lake was frozen solid. Cornfields provide additional appeal to the Missouri landscape from a swan’s perspective; quite a few photos accompanying eBird observations show swans congregating in corn stubble, presumably feasting on high-calorie leftovers well-suited to propelling a 20+ pound bird in flight. Though many individuals migrate to Missouri, there are plenty that stay behind in more northerly locations. Trumpeters that overwinter along the Mississippi River in Monticello, Minnesota have become a tourist attraction promoted by the Chamber of Commerce; there’s even a swan webcam. There, too, they appreciate corn, in that case doled out on a daily basis by a dedicated swan lover. Trumpeters’ taste for corn, whether served up bird-feeder style or left over from large-scale agriculture, is a reminder that the birds we see today may be breeding without direct human intervention, but they still receive a form of human assistance; we haven’t magically returned to the 1800 ecosystem.

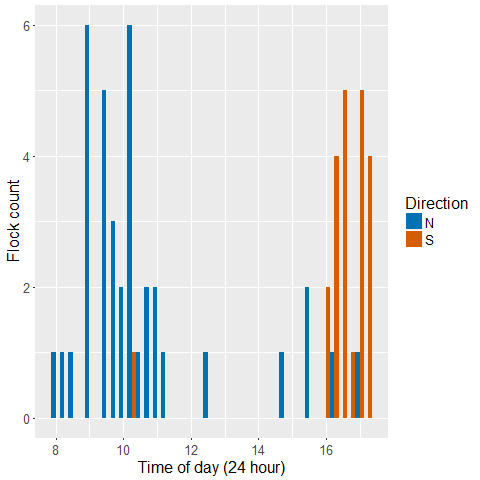

Water and corn are the resources that we suspect are motivating Trumpeter Swans to fly over our property routinely in recent winters. But that’s still a working hypothesis, and we hope some readers may help us discover more conclusive answers. Here’s what we know: We see them frequently in the winter, but not necessarily daily. When we do see them, there’s a pattern to their activity. Most sightings in the morning are of northbound flocks, and most sightings in the later afternoon are of southbound flocks (see figure below). As we both work from home, are frequently outdoors, and can hear flocks from indoors, we’re reasonably comfortable with the scope of our observations and records. Since last January, we’ve been detailed taking notes about flock size, timing, and direction, though we haven’t gotten all of these incidental reports into eBird yet. Though we tend to think of them as “commuter swans”, a sighting in the morning doesn’t guarantee that we’ll see them heading “home” in the evening. But we also know that their flight path can cover a swath that extends beyond our viewshed; we’ve seen them repeatedly fly over the house of friends located about half a mile to our west. Flock sizes between 6 and 12 birds are typical, but we’ve seen as few as two and as many as 30+ flying as a flock. On January 6, 2018, we had our record high count to date, with 59 Trumpeters flying north around 9 a.m. within the span of a few minutes.

Flight direction of Trumpeter Swan flocks by time of day as observed from our northern Boone County (MO) property, Jan., Feb., & Dec. 2017 and Jan. 2018. Swans tend to be north-bound in the morning and south-bound in the afternoon, with occasional exceptions. Plot by Joanna Reuter.

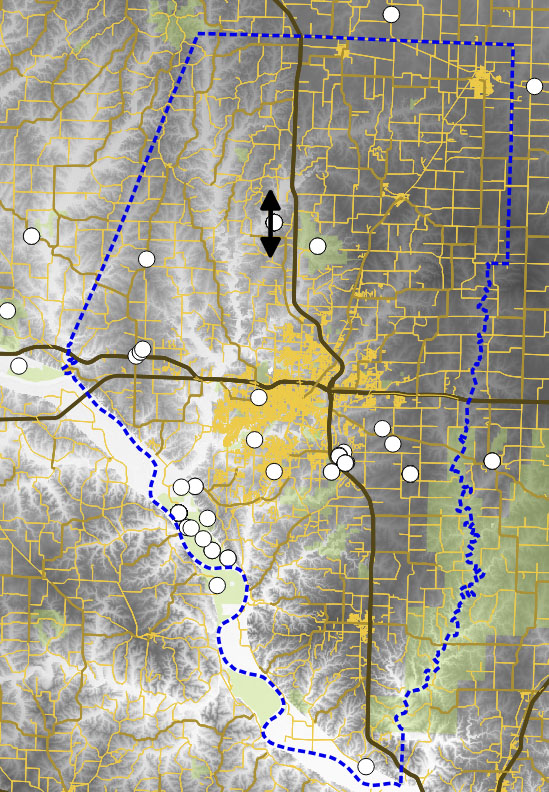

We suspect that weather affects their movements, though so far we haven’t identified definitive trends that let us predict when we’ll see them. Our limited attempts to scout areas to our north and south haven’t yielded answers on their destinations, and there’s a gap in eBird observations around us, particularly on the flight trajectory that we most commonly observe (see map below). This unpredictability, and our own busy lives, have kept us from undertaking serious searches. I dream of GPS- or Motus-tracking these birds, but in the meantime, old-fashioned observations and persistence are the tools available. If you have time to dedicate to solving the “mystery of the northern Boone County swans”, by all means, be in touch.

Trumpeter Swan reports (white dots) in or near Boone County as reported on eBird (through Nov. 2017). Arrows show approximate dominant flight direction as observed from our property in northwest Boone County, MO. Sighting data source: eBird Basic Dataset. Version: EBD_relNov-2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Nov 2017. Map by Joanna Reuter

February continues to be a good month to view Trumpeter Swans in Missouri, so get outside and see what you can find. With a little luck, and maybe some guidance from eBird, you’ll be able to enjoy these birds with relative ease. But also think about what the future might be like for Trumpeter Swan populations. They’ve made a remarkable comeback, but will new problems arise? Will disease, climate change, lead poisoning, or other issues once again threaten population vitality? Or might we be on a path toward too many Trumpeter Swans? Already, some wild rice stands on northern lakes are being overgrazed by swans, frustrating local harvesters and leading to discussions of hunting. If “too many swans” seems unthinkable, consider the Canada Goose, another large waterfowl that made a remarkable comeback only to became an abundant and despised nuisance to many. Regardless, admire the swans for what they are now: Not so much a wild species that takes us back in time to a mythically pristine past, but a modern success story of a species given a helping hand by dedicated humans; a species that has adapted to modern conditions; and a species whose future and success are intertwined in complex ways with our own.

© Joanna Reuter 2018