Birds in Big Numbers: September Broad-winged Hawk Migration

by Joanna Reuter

by Joanna Reuter

Although a variety of raptors migrate south in the fall, Broad-winged Hawks do so in groups that sometimes number in the hundreds or thousands in Missouri. Getting to see “kettles” of Broad-winged Hawks riding thermals and/or cruising south is a thrilling and memorable experience.

High count: Described as “the most extraordinary wildlife spectacle that either of us has seen,” the September 24, 2017 observation by Pete Monacell and Austin Lambert was record-setting for Missouri. They conservatively estimated six thousand Broad-winged Hawks at the City of Columbia Wetland Cell #1. Here’s their description from eBird:

Just after 11:00, while completing the loop around the wetland cell, we began to notice a large influx of Broad-winged Hawks flying overhead on a southerly bearing (we had seen one previously). As the BWHA’s streamed over us, in a ribbon that often filled out scopes, we continually revised our estimate upwards. The overhead ribbon of BWHA’s lasted for more than ten minutes, and the birds did not pass out of view for more than twenty minutes. Finally, we agreed upon a conservative estimate of 6,000 birds, and would stress that this is conservative, and that there were likely more than this. We feel very privileged to have seen this natural spectacle and are still in awe of it. eBird list

Here’s one photo from that record day (with more available on the eBird list):

Other big days, 1000 or more: In the CAS six-county area, the above record is the only one on eBird that reports more than one thousand Broad-winged Hawks. Missouri as a whole has 3 additional eBird records of such stunning numbers:

- 4,120 September 23, 2018 Webster County eBird list

- 1,000 September 22, 2018 Greene County eBird list

- 1,228 September 27, 2017 Gasconade County eBird list

Edge Wade described the Gasconade County observation as follows:

“10:30-10:40: We caught sight of a flight of moderately high 22 Broad-wings, then another two fairly low, and we looked up. It reminded me of an old black and white movie about the bombing raids on Germany that took off from England–wave after wave of planes in loose formation. Way, way up was a massive flight of BWHAs heading due south.”

These sightings happen to be from the last two years, but older observations of thousands of Broad-winged Hawks can be found in the archives of The Bluebird, newsletter of the Audubon Society of Missouri (see resources at the end of this article).

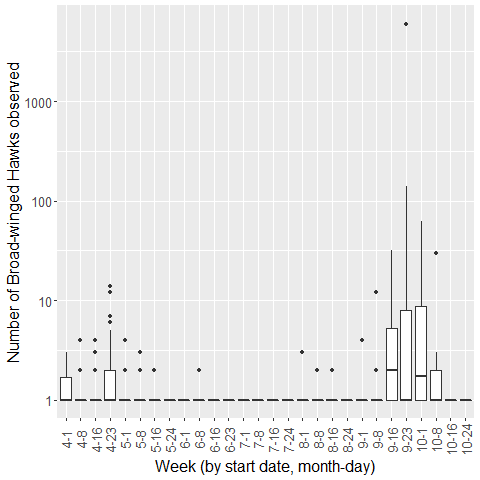

This plot shows the timing and magnitude of Broad-winged Hawk (BWHA) observations, as reported on eBird, in the six-county area served by CAS. Within each week, all reported BWHA observations are tabulated and presented as a box-and-whisker plot. Note that the y-axis is a log scale. Spring migration occurs in April and early May, and most spring-time lists that report BWHAs show fewer than 10. Some Broad-winged Hawks do nest here, and summer reports generally tally just one or two BWHAs at a time. In the fall, numbers increase as south-bound Broad-winged Hawks pass through. Based on existing eBird data, the peak week begins on September 23; it was during this week that the record 6,000 hawks were observed (point at the top of the graph).

Other big days, between 100 and 1000: The CAS six-county area has one eBird report in this category: 140 Broad-winged Hawks by CAS board member Greg Leonard from Nifong Park in the early afternoon of September 24, 2018 (eBird list). Since 2010, the state of Missouri has had at least one eBird report per year of 100 or more. Of course, not all observations make it into eBird: reports are skewed toward recent years and some are not entered at all. I write this with a guilty conscience as Eric and I saw an estimated 200 Broad-winged Hawks during the late afternoon of September 22, 2018, an experience that blew our minds and that we reported on MOBIRDS, but did not report on eBird.

When (dates): Based on eBird data, the best chance of seeing large numbers of migrating Broad-winged Hawks in central Missouri occurs during a time window starting around the fall equinox and continuing through about the first week of October. Peak dates are roughly from September 22 to 27; all eBird reports in Missouri for totals exceeding 1,000 fall within this range, as do most reports of 100 or more.

When (weather): All days are not equal within that window; weather matters for migrating birds. The general consensus is that conditions optimal for migration follow the passage of a cold front, when winds are generally out of the north, helping the hawks move southward with a minimum of effort. These conditions tend to be good for hawk watchers as well as hawks: the heat breaks, the sky is clear blue, and the thought of spending time outdoors is enticing.

Don’t just think about local weather, though. Most of these hawks began their journey well to our north, and weather elsewhere along their route may affect their path and progress. Also keep in mind that they are on a long journey to South America, going all that way on a schedule that is relatively predictable from year to year. Really lousy weather may slow their journey, but hawks probably don’t have the luxury to wait around and migrate only on perfect days. Weather matters, but the details are complicated.

When (time of day): There’s no need to be out at the crack of dawn. Broad-winged Hawks roost in forested areas overnight and migrate during the day, making use of thermals that develop from solar heating. They can potentially be seen throughout the day, from mid-morning takeoff to late daytime landing. Hawk watchers sometimes experience a mid-day lull, perhaps because hawks can achieve elevations above our visual range (as discussed in this book review).

This plot is similar to the previous one, except that it draws from BWHA observations for all of Missouri, and it presents day-by-day data from early September through mid October. There is a distinct peak in late September, as well as a tail that extends into early October; perhaps some of the October sightings relate to birds that were delayed by weather?

Where: Famous hawk-watch sites combine a good view of the sky with geography that concentrates birds and/or topography that is conducive to generating lift. Missouri does not have landscape features sufficient to concentrate migrating hawks in any known location, so settle on a place with a good view of the sky that will be enjoyable even if you don’t see a single raptor. Eagle Bluffs or Columbia’s Wetland Cells combine sky views with other good prospects for birding. If you feel like an upland hike, a good choice could be a relatively open trail, such as the Grasslands Trail at Rock Bridge State Park or some of the hiking trails at Rocky Fork Lakes Conservation Area. Alternatively, an urban rooftop could be effective, an approach we’ll test out during September’s Hawk Watch Happy Hour event. Or you can simply pay attention anytime you happen to be outside in late September. Glancing up from a parking lot at the right time could be as rewarding as staking out a blufftop all day.

Bottom line: Seeing a really big flight of Broad-winged Hawks in Missouri is a bit of a long shot on any given outing, but the potential reward is worth the effort. It helps that the time frame when big numbers are most likely to move through in the fall is pretty narrow. Monitoring the MOBIRDS listserv and/or the Columbia Audubon Facebook group may tip you off to migration activity that others have observed. No matter what, late September is often a nice time of year to be outside anyway, so why not make a point of doing so with an eye to the sky, especially if a nice cold front comes through and provides conditions that are great for both you and, very possibly, migrating hawks? With some luck, you might experience something amazing.

Data source: Figures produced using data from the eBird Basic Dataset. Version: EBD_relMay/Jun-2019. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. May/June 2019.

Bird-nerd bonus: I made a variety of plots from the eBird data that didn’t make it into the article. If you want to see some of these, take a look at this addendum. (Analogous to the special features on a movie DVD, the production quality isn’t top notch, but those with a deep interest will likely gain something from the content anyway.)

Learn more: Here are some additional resources to explore:

- Actual tracks of Broad-winged Hawks migrating from Pennsylvania to South America: The technology to track individuals over the course of migration is amazing, as is the information embedded in these tracks. Here’s the overview page for the project, a Google map of actively tracked hawks, the Movebank website with full migration history of tagged Broad-winged Hawks (fully and freely downloadable), and a blog post about the first males to be tagged.

- Weather visualizations, past, present, and near future: Try this site to visualize weather systems including wind fields at various heights in the atmosphere, precipitation, and much more. Useful for deciding when to hawk watch or for making sense of your observations after the fact.

- Identification: Here’s an ID fact sheet for Broad-winged Hawks from Hawk Watch International. The Hawk Migration Association of North America offers these ID materials.

- Thermals: The explanations and illustrations of thermals at this site are helpful for understanding hawk migration.

- Pre-eBird records: Three days with observed flights of over 3,000 Broad-winged Hawks from the pre-eBird era are noted in The Status and Distribution of Birds in Missouri (a downloadable, open-source publication). The archive of The Bluebird contains multiple issues that note or describe observations of large numbers, including: Dec. 1977, Dec. 1986, Dec. 1992, and Dec. 1993 (not a comprehensive list).

Text and plots © Joanna Reuter 2019