Bird Watching in Chile

by Joanna and Eric Reuter

-by Joanna & Eric Reuter

We recently had the good fortune to travel through the southern half of Chile, learning much about its ecosystems, history, and culture along the way. Though we mostly explored on our own using Chile’s excellent bus network and our own feet, a day spent with Raffaele Di Biase of the excellent BirdsChile guiding service allowed us to access new places and species while learning from his extensive knowledge of the country. We didn’t plan to photograph birds, given our basic camera equipment. However, many birds were surprisingly tolerant of human presence, and we couldn’t resist taking photos when opportunities arose (all images in this story by Joanna or Eric Reuter).

Camera-friendly Chilean birds. From upper left to lower right: Black-faced Ibis, Rufous-collared Sparrow, Neotropic Cormorant, Eared Dove, Kelp Gull, Chimango Caracara, Upland Geese, Magellanic Penguins.

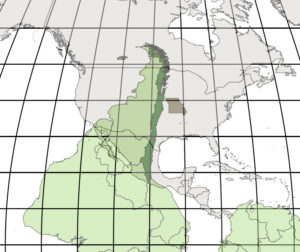

A south-up rendering of South America providing latitudinal comparison with North America (Chile in dark green). Longitude has been shifted for ease of comparison.

Even at its widest, Chile is narrower than Missouri (~221 miles vs. ~240 miles), yet a great deal of interest is packed into this slender strip of land between the Pacific and the Andes. Chile is almost nine times longer than Missouri, with a latitudinal range roughly equivalent to that of Mexico City to Edmonton. The country contains everything from extreme deserts to temperate rainforests to glaciated terrain, and within these diverse habitats are a variety of interesting and unique birds.

Geography affects the dynamics of songbird migration in the southern hemisphere, and the result is not simply an inverse of the patterns we see here in Missouri. Unlike the northern hemisphere, where the land area available for songbirds is abundant at high latitudes, South America narrows dramatically. Think of all the warblers that move through Missouri in spring heading for the vast boreal forests of Canada; South America doesn’t have an equivalent. Some songbirds do migrate latitudinally, and the Andes also provide an opportunity for some species to seasonally change elevation as a proxy for latitude. As Alvaro Jaramillo’s excellent guide Birds of Chile notes, “Careful research on southern (austral) migrants is a new field. For most Chilean species migratory routes and timing are very imperfectly known.”

To a North American, an old-growth Chilean forest looks other-worldly, with trees that are entirely unfamiliar even at comparable latitudes to home. This is a stark contrast to Europe, where many trees are recognizable to a North American naturalist. There’s a tectonic reason for this: 180 million years ago, South America was joined with other present-day southern hemisphere landmasses (including Australia) in the Gondwanaland supercontinent, while it only became joined with North America around 3 million years ago. Thus, the continent’s flora and fauna share common evolutionary ancestors with the former, manifested today through biologic specialties including marsupials (our opossums originated in South America) and distinctive southern hemisphere trees such as Nothofagus and Araucaria (see photos). Tectonics continue to shape Chile’s present landscape, with an active subduction zone along the coast that continues to drive volcanism and uplift. The Andes and the ocean have kept Chile relatively isolated for millions of years, resulting in a variety of endemic plants and birds.

Trees of south-central and southern Chile. Araucaria araucana trees (left two photos) grow in a narrow geographic zone mostly in the Andes. Trees of the genus Nothofagus (southern beech, right 4 photos) dominate southern Chilean forests, though they have diverse morphologies.

Traveling to a distant country is an exciting opportunity for a bird watcher, and the prospect of learning a multitude of new birds is exciting yet daunting. Adding to the challenge, Birds of Chile presents three names for most species: English, Chilean/Spanish, and scientific. We enjoyed learning and using as many Chilean names as we could, many of which originate in indigenous names. Many make good use of onomatopoeia: Pitío, for example, is the Chilean Flicker, and learning this gave us hope that some knowledge of bird sound would remain relevant between hemispheres. Others Chilean bird names are eminently sensible, such as Carpintero Negro (literally “black carpenter”), for the Magellanic Woodpecker, a large, charismatic, and (mostly) black woodpecker. Others are just practical; who wants to utter the ubiquitous but multi-syllabic Rufous-collared Sparrow or Chimango Caracara when Chincol or Tiuque will do just fine?

Chile does have a variety of birds that are familiar to Missouri birders; we saw just over a dozen species that were already on our life lists. These fit into a few categories:

- Birds that breed in the northern hemisphere and “overwinter” in the Chilean summer, such as Greater Yellowlegs, Franklin’s Gull, and Whimbrel. The only species that breeds in Missouri with some individuals overwintering as far as Chile is the Barn Swallow (though we didn’t see any).

- Birds with ranges that extend across large parts of the Americas, including Turkey Vulture, Black Vulture, Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Black-crowned Night-Heron, and the ubiquitous House Wren.

- Birds that are invasive, including House Sparrow, Rock Pigeon, and Cattle Egret.

The ~80 new life species we saw during the trip included an assortment of birds that were somewhat familiar, such as:

- The Austral Thrush is in the same genus as the American Robin, which it resembles in song, habit, and habitat use.

- The Long-tailed Meadowlark resembles an Eastern or Western Meadowlark, if you replace the yellow and black breast coloration with brilliant red and darken the back a bit (though by current taxonomy they do not share the same genus).

- The Ringed Kingfisher resembles the Belted Kingfisher, though larger and with a bit more color.

However, the most exciting Chilean species for us were those with no equivalents in our region; highlights included:

- Darwin’s Rhea, an ostrich-like bird that we saw only through bus windows but were stunning nonetheless.

- Chilean Flamingo. Sure, Florida has flamingos, but in Chile you can go to the latitudinal equivalent of southern Hudson Bay, drive though a landscape reminiscent of Wyoming with Nothofagus trees that are shaped a lot like junipers, and see lakes dotted with pink flamingos.

- The Chimango Caracara (Tiuque) is a ubiquitous but never-boring bird. Its hawk-like appearance (sharp bill, talons) belie its mild, playful personality and scavenger nature, behaving more like a cross between a robin and a crow. We never tired of seeing fierce-looking “hawks” meekly digging up earthworms or tumbling acrobatically across the sky.

- Perhaps our favorite group of unusual birds were the tapaculos (family Rhinocryptidae), most of which are South American and especially Andean. As noted in Birds of Chile, these are “suboscines infamous for their vocal but frustratingly skulking nature.” We had great looks at several Chucao Tapaculos in three national parks, but the only likeness we could photograph was a mural in Puerto Montt (see photo below). The more elusive Black-throated Huet-huet spends quite a bit of time on the ground, foraging with its feet and leaving patches of bare soil (see photo). We had some excellent—but always brief—looks at these awesome birds, whose distinct vocalizations are a memorable experience as they echo through steep mountain valleys. A third species, the Magellanic Tapaculo, may have tricked us into thinking it was a mouse. We saw three small grey creatures streak into view maybe 10 feet away. First instinct: bird. Moment later: no, not bird, they disappeared into holes in the ground, they must have been mice. Field notes: “rodent-like critter x3 in cane thicket, grayish, 4 inches long, fat mouse size.” Later, we re-read the description in the bird book: “Mouse-like behaviour, creeping close to ground and even under debris.” Size: 4-5″. Can’t be 100% sure about the sighting, but at least we know we did later hear the Magellanic Tapaculo on our day with Raffaele.

Of all the diverse birding opportunities in Chile, none was as memorable as visiting the Magellanic Penguin colony on Isla Magdalena (within a Chilean national park in southern Patagonia). Visitors are given an hour to walk an 850 m trail through actively nesting penguins and Kelp Gulls. These birds are quite tolerant of the carefully managed visitation. The penguins nest in burrows excavated from the loose but rocky soil; some were actively expanding their burrows, kicking dirt a few feet into the air. We were told that there were 2-week-old chicks, but none were visible from outside, though we did see untended eggs in one nest. Adults were often visible in the burrows, either incubating eggs or keeping young chicks warm and safe from the Chilean Skuas that were scouting for a meal of penguin chick.

While tourists gawk along the trail on Isla Magdalena, Magellenic Penguins go about their business of nesting, hunting to obtain food for chicks, and protecting nests from Chilean Skuas.

Some adults were cycling between nest and open water, seeking food for hungry chicks; they would happily waddle along the trail while ignoring human visitors, much like bison blocking traffic in Yellowstone. Many adults were vocalizing: some by a sort of guttural hooting, with the chest expanding and contracting each time, and others (probably mated pairs) made chattering sounds, often while nuzzling or otherwise interacting. Ironically, we didn’t get a single life species on this day as we’d already observed every species present somewhere else, though not as delightfully or closely.

Chile is an extraordinary country and a wonderful place to visit for naturalists (including bird-watchers) given its extremely diverse ecosystems, abundant national parks and protected areas, and excellent public transportation network. Many local folks we met (guides, park rangers, small hostel owners) emphasized the importance of eco-tourism as a way to fund and support conservation in the country and build a culture that can counterbalance more problematic economic development. Going off the beaten path is especially rewarding, as popular destinations like Torres del Paine National Park are being loved to death by hordes of visitors, but there remain vast swathes of public land throughout much of the country that are free of crowds. These places allow naturalists a much more peaceful chance to interact with the landscape while supporting local efforts to boost sustainable tourism. If any readers decide to go, please feel free to contact us for ideas and advice.

© Joanna & Eric Reuter 2019