Watch for Nesting Activity this Spring and Summer

by Joanna Reuter

by Joanna Reuter

During the pandemic, many of us are likely to find that birding involves regular visits to local spots rather than far-flung adventures to distant destinations. One way to make the most of this is to pay special attention to nesting patterns and savor the benefit of being able to follow a year in the life of a bird family (or many). Here are a few observations and musings regarding the rewarding hobby of nest watching:

Nest materials

Last spring, Eric & I observed some interesting uses of nesting materials. Here are three brief accounts:

Blue-gray Gnatcatchers build small cup nests on open branches. Finding one of these nests poking up from a branch is a treat; viewed through binoculars, the lichens coating the outside of the nest are visible. What other materials go into the nest? Last year, we got a partial answer as we watched a gnatcatcher harvest the silky tufts from the seedpod of a dogbane plant (Apocynum cannabinum); it then carried the material to the nest and incorporated it into the lining. Blue-gray Gnatcatchers build small cup nests on open branches. Finding one of these nests poking up from a branch is a treat; viewed through binoculars, the lichens coating the outside of the nest are visible. What other materials go into the nest? Last year, we got a partial answer as we watched a gnatcatcher harvest the silky tufts from the seedpod of a dogbane plant (Apocynum cannabinum); it then carried the material to the nest and incorporated it into the lining. |

Deer are a real problem on our farm, and folk wisdom suggests putting human hair on fences as a repellent. Does it work? I have no conclusive data. But, hey, what else is there to do with the material that accumulates in my hairbrush? Last year, a side benefit came out of this method, as a Northern Parula identified these hair clumps on our vegetable field fence as a source of nesting material. Here are some notes from my eBird list from May 5, 2019 that accompany the report of Northern Parula with a breeding code of “” (full list here): Deer are a real problem on our farm, and folk wisdom suggests putting human hair on fences as a repellent. Does it work? I have no conclusive data. But, hey, what else is there to do with the material that accumulates in my hairbrush? Last year, a side benefit came out of this method, as a Northern Parula identified these hair clumps on our vegetable field fence as a source of nesting material. Here are some notes from my eBird list from May 5, 2019 that accompany the report of Northern Parula with a breeding code of “” (full list here):

|

The third case was particularly curious. During the 2018 growing season, I had a variety of cucurbits including gourds and bitter melons growing on a trellis in the garden. Come spring 2019, I had cleaned off the bulk of the vegetation, but many tight-clinging tendrils remained. Much to my surprise, as I worked in the garden, a female Summer Tanager started coming to that trellis to collect tendrils. She was particular, as indicated by notes from my May 14 eBird list: The third case was particularly curious. During the 2018 growing season, I had a variety of cucurbits including gourds and bitter melons growing on a trellis in the garden. Come spring 2019, I had cleaned off the bulk of the vegetation, but many tight-clinging tendrils remained. Much to my surprise, as I worked in the garden, a female Summer Tanager started coming to that trellis to collect tendrils. She was particular, as indicated by notes from my May 14 eBird list:

|

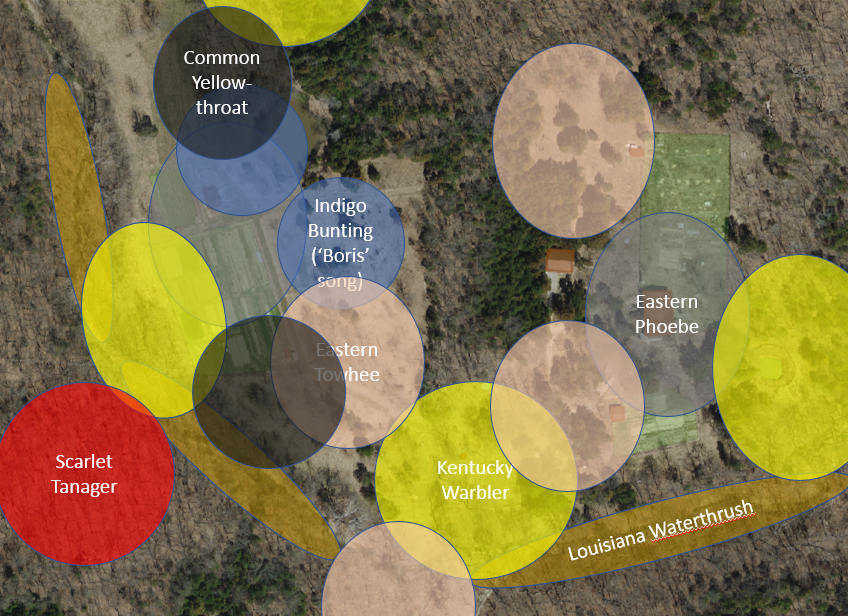

Inferring territories

Identifying nests

Nests can be challenging to identify. One of the easiest ways to identify a nest is to identify the bird that is using it, but sometimes that is not possible. Another good resource is the Macaulay Library, which has search functions that allow for filtering for photos of nests of a given species. Photos can be submitted to the Macaulay Library simply by attaching them to an eBird list.

Citizen science opportunities: eBird and NestWatch

A couple methods exist to report observations regarding nesting through citizen science platforms.

NestWatch has a detailed protocol that entails repeated nest visits and tracking of nest outcomes, with guidance on the care necessary to minimize chances of negatively impacting the nest. It is a great option for nests that are positioned such that eggs and young can be counted, and for people who have time and mental energy to keep track of nest visit schedules.

Another option is to report through eBird, making use of the breeding codes and note-taking opportunities it provides. The breeding codes are explained in more detail on this eBird help page. Though eBird does not yet summarize breeding codes in an easy-to-view way on the website, these observations contribute useful data about breeding activity of birds worthy of future analysis.

© Joanna Reuter 2020

Watching a warbler using some practiced acrobatics to show up a clumsy titmouse was a lot of fun. And I love the thought of baby parulas in a nest lined with my hair!